The Internet Archive’s rehauled GIF search engine opens a portal to Web 1.0’s visual culture

Your TL;DR Briefing on things worth tracking — and talking about over your next power lunch. *Wink.* This time the thing is vastly improved GIF archaeology via the new GifCities search engine plus a short history of GeoCities cyber neighborhoods and the case for reclaiming the “netizen” label.

The thing is:

Until recently, finding early internet GIFs of drag queens presented numerous challenges — chief among them, dragons.

The GifCities search engine has since 2016 empowered hobby GIF collectors, internet artists and, yes, this writer to find GIFs archived from 1990s and early 2000s GeoCities websites. Rather than using the Archive’s Wayback Machine to manually click through countless webpages, as you once needed to do, GifCities let you search through millions of old GIF files — those rudimentary animations that were arguably the defining visual element of the World Wide Web for more than a decade. Since launching for the 20th anniversary of the Archive, the search engine has earned a cult following among creatives of all stripes. GIFs resurfaced through GifCities have appeared in viral news articles (remember the wild digital art direction from this 2018 New York Times feature on the Royal Wedding of Prince Harry and Meghan Markle?) and art projects (such as this 2016 exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum).

Assorted GIFs of dragons.

The first version of GifCities used “file name” text search, which worked fine for more generic or popular categories of GIFs, but proved troublesome when you wanted to identify more niche GIFs. This also made it feel unintentionally gamified and a bit addictive if I’m honest — like you were treasure hunting for nuggets in the archives, hacking your way to uncover something in the dirt that few people had the patience to unearth.

For instance, if you entered the query “drag queen,” you’d mostly see dragons.

You had to really sift through the dragons — and sometimes Queen, the band — to find any queens.

But on Monday, June 9, the Internet Archive shipped a new version of the GifCities search engine — the biggest update since it launched almost a decade ago. The marquee update, among several other features (including a “GifGram” e-card maker), is semantic search.

Early internet drag queen GIFs. Some queens even had fan sites dedicated to them on GeoCities back in the day.

That means, now when you type in a query, the results are no longer based on file name alone.

Therefore, today, when I typed in “drag queen,” I got a higher proportion of actual drag queen GIFs in the results — and far fewer dragons.

The thing about that is:

Early internet GIFs were once novel ways for a massive wave of newbie netizens to express themselves through their “home pages.” On July 5, 1995, the little-known Beverly Hills Internet (BHI) company announced in a press release that it was “offering cyber citizens the first homesteading program of its kind on the web,” as it brought online four more “cyber cities,” where anyone with a personal computer could, ahem, grab some land. (Fun fact: Days later on July 28, 1995, the nerdy action-thriller “The Net,” starring Sandra Bullock, was released.)

GIFs of Sandra Bullock and "The Net" film. The two most "modern" GIFs are contemporary. The "Queen of the Web" GIF comes from a GeoCities fan site dedicated to Bullock.

“The homesteading program enables anyone with access to the Internet to have a free Personal Home Page, or GeoPage, within our cityscapes,” BHI president David Bohnett said in a press release (archived via the Wayback Machine). Indeed, physical metaphors for early cyberspaces were all the rage in the mid-’90s, and nobody employed them better than Bohnett. The release read, “BHI is in the business of building online GeoCities — cyberspace communities of netters who have their own home pages, create their own content, reside on cyberstreets resonantly named after landmark thoroughfares from around the world.” (Netter has largely fallen out of favor, but was used synonymously with other ‘90s web lingo such as netizen and cybersurfer.)

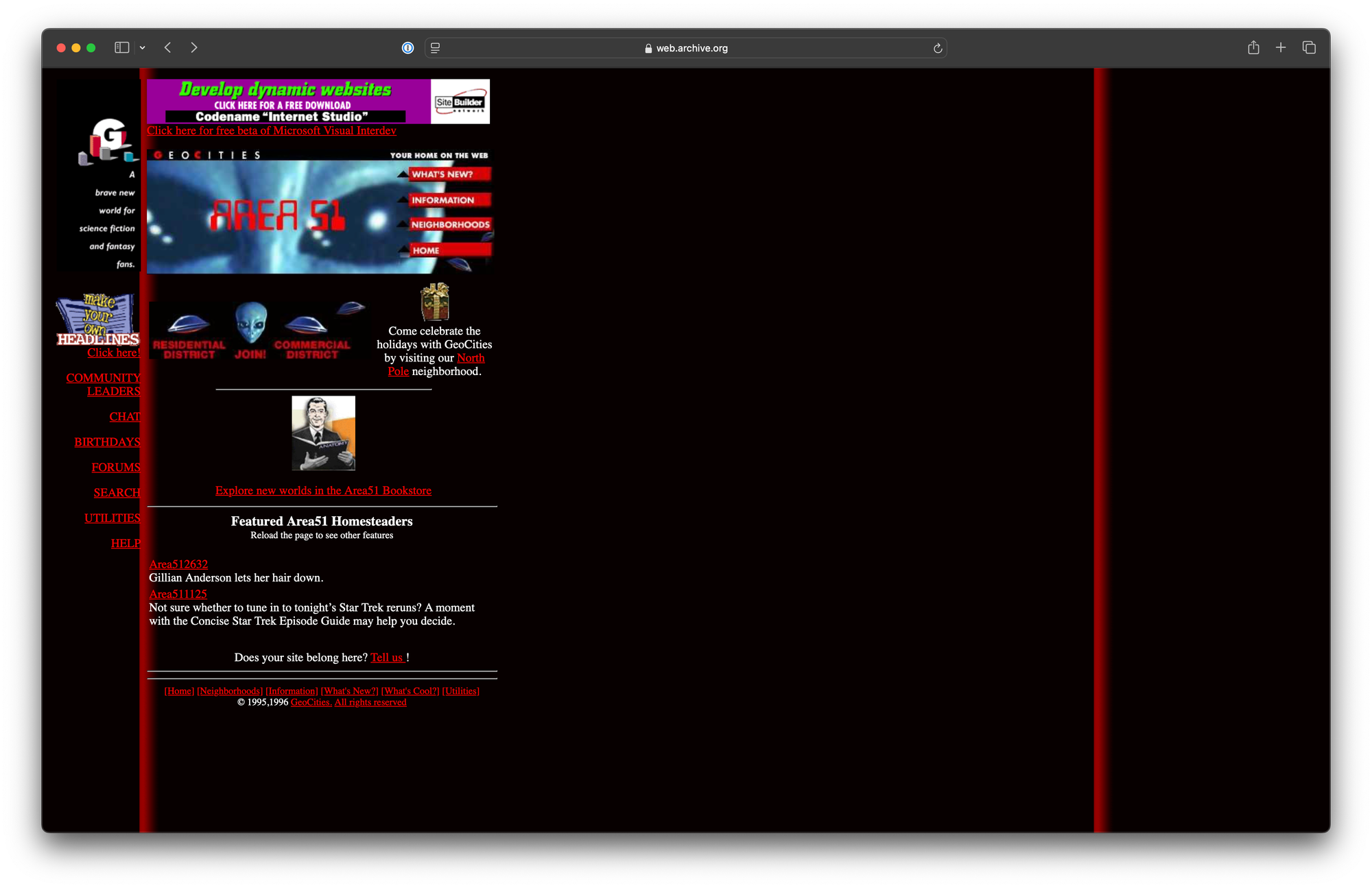

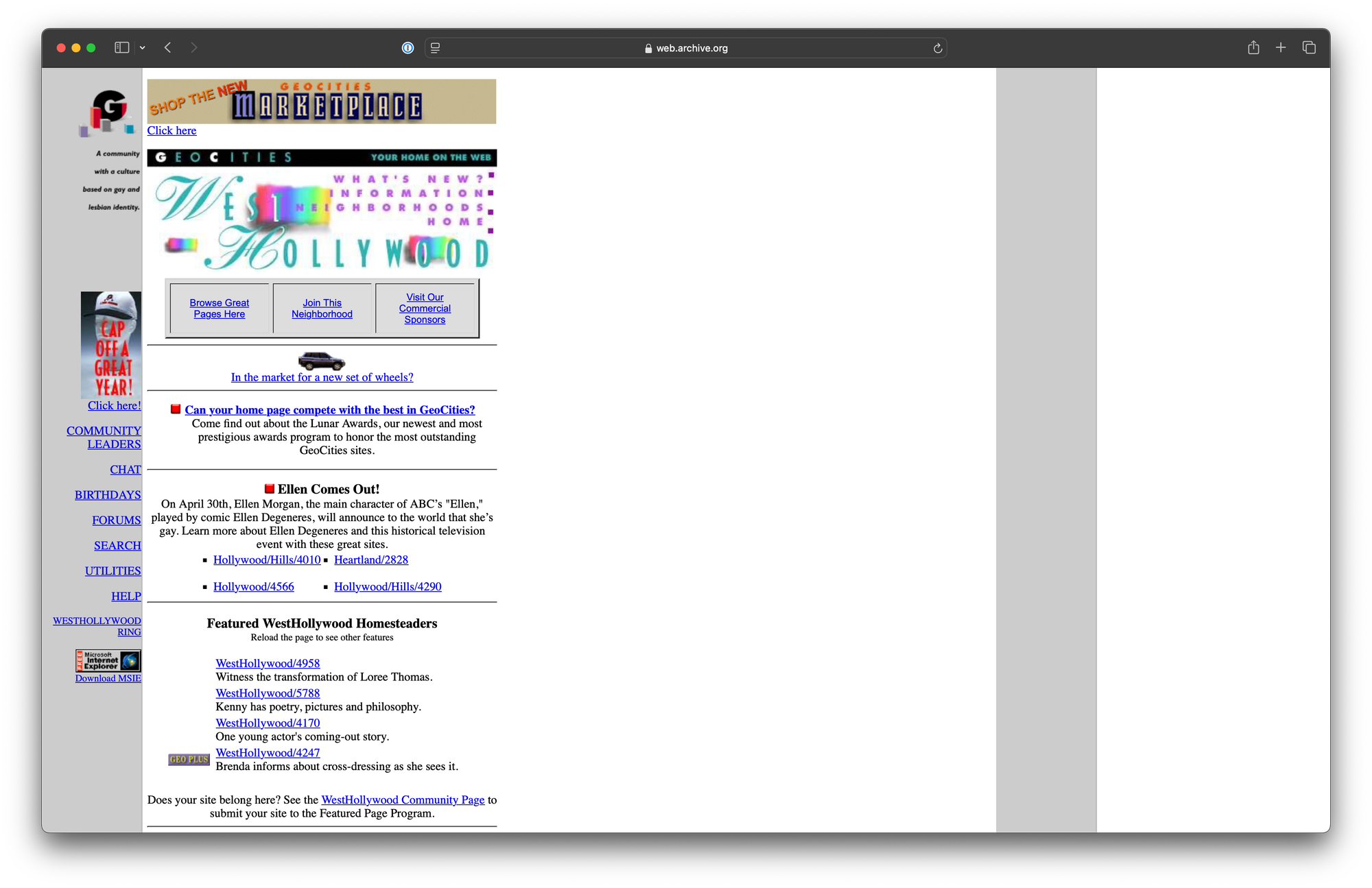

One big news item was those new “cyber cities” — Silicon Valley, Capitol Hill, Paris and Tokyo joined the existing GeoCities of Hollywood, Rodeo Drive, Sunset Strip, West Hollywood, Wall Street and the Colosseum. Finance bros hung out on Wall Street, pop culture mavens flocked to Hollywood and the cyber-cruising queers gathered in cyber WeHo, the dot-com counterpart to the Los Angeles gayborhood. (GeoCities had virtual gay spaces from the start, which makes the fact that Bohnett is gay relevant.)

But the update that shifted the trajectory of the young Los Angeles-based tech company was a page builder. The release went on: “BHI has introduced a Personal GeoPage Generator that enables homesteaders to create their own home pages in minutes, complete with color graphics, links to their favorite web sites and any personal data they want to share with the virtual world.” (Color graphics! Wild!)

In many ways, GeoCities is often described as a precursor to social media due to its index of pages grouped into cities and neighborhoods, and that’s true. Though in reality it was primarily a personal page builder and website hosting site. In this way, GeoPage Generator was the precursor to today’s so-called “no-code” site builders and professional web design platforms (including Webflow, Framer and, most recently, Figma Sites).

Before BHI’s simple site-building tools, the primary way to publish a personal website was learning to code HTML, an arguably simple markup language but a technical barrier that essentially gatekept personal pages to those who knew the language. BHI wasn’t the only company aiming to make personal websites widely available, but they were the most successful early on. Soon, thousands of newbie homesteaders each day were launching basic, messy pages all overflowing with GIFs. By December that year, BHI’s popularity had exploded and the company rebranded as GeoCities, as most will remember it.

With the influx of users who didn’t know HTML, the visual culture of the web changed. Rather than personal pages for developers and academics, GeoCities websites took the form of fan pages, themed sites dedicated to everything from pet projects to actual pets, portfolios for the first wave of online freelancers, and so forth.

Many netizens don’t realize that what we now commonly refer to as GIFs are primarily looping videos mimicking the original file type, which has mostly faded into obscurity. Today when we say “GIFs” we’re more accurately referring to “clips” of pop culture and video memes — something we might send in a text message or drop in a reply on social media.

Early internet GIFs, on the other hand, served more purposes than that. Surely, the early waves of netizens GIFed any celebrity of note. But pop culture GIFs could be as reverent as subversive. And more notably, GIFs were a kind of clipart, often purely decorative. Their low file size allowed them to load on slow dial-up internet connections, and the animations felt fresh. The file type emerged as a precursor to the online “personal brand,” a way to express your interests, aesthetic and, indeed, humor through your curation.

With the influence of the GeoCities page builder, GIFs also became the functional architecture for early websites — buttons and navigation, page spacers and dividers.

Buttons, calls to action and a little shade were all a part of the diverse ways early internet GIFs appeared in GeoCities websites.

The GIF’s dominance wasn’t accidental. Built around Lempel-Ziv-Welch compression, an algorithm that could pack complex color images into tiny files, GIFs had what amounted to superpowers in the dial-up era. The format had emerged from a team at CompuServe led by Steve Wilhite, who died in 2022. But where network limitations had partly fueled GIFs' popularity, GIFs became less necessary as connection speeds increased and web design evolved.

Eventually, both GIFs and the GeoCities pages housing many of them became cringe — signs of having poor taste.

As the social and app-driven Web 2.0 era emerged, the online realm started to feel less DIY and more like a sanitized shopping mall, controlled by a smaller handful of corporations. The zany aesthetic of the dot-com boom became uncool. Partly because of the garish colors and old-fashioned animations, GeoCities websites became an example of bad design, too. As Facebook pushed everyone to express themselves primarily through photos and microblogging, the user interface of the web shifted toward homogeneity. Squarespace’s signature white space and sleek minimalism ruled the new wave of personal branding.

By the time Yahoo, which had acquired GeoCities, shut the service down on October 26, 2009, the physical metaphors of early cyberspace seemed equally dated. At that point, few personal websites had an “under construction” section. The internet was increasingly commercialized, less handmade and therefore the GIF construction guys were largely out of work.

So many early internet construction workers GIFs remain out of work to this day.

Where things get interesting:

I’m not exactly sure when early internet GIFs began to dominate my entire personal brand, but I can trace it back to the early days of lockdowns when, with my freelance projects largely canceled, I found myself seeking some form of escapism from the news.

Inspired both by my coming of age with the internet and the GIF-y work of internet artists like Olia Lialina and Cameron Askin, I became fascinated with the wide range of things that had been GIF’d, as I told Chris Freeland, director of the Internet Archive’s library services, in an article for the Archive’s blog last year:

That nostalgia for the version of the internet they grew up with is what first sparked Shadel’s interest in collecting old-school GIFs. During the first months of pandemic lockdowns in 2020, Shadel started spending a lot of their extra spare time diving deep into the Internet Archive’s GifCities collection. Shadel’s personal fascination began with under construction GIFs, a rich niche in the collection full of animated construction workers and tools. Then came seeking out GIFs of Furbies, Tamagotchi and other cultural touchstones that they came of age with online. Over the next few years, downloading and organizing GIFs became a hobby for Shadel.

Yes, I redesigned my website, inspired by the 1996 Space Jam site and filled it with some of my favorite cyberspace-themed GIFs including a bubble-gum blowing Furby. And when I launched ESC KEY .CO, I integrated GIFs into long-form articles as both art and section dividers, riffing on the structural utility they played in early internet websites. My personal GIF collection has only continued to grow.

And in October 2024, I contributed to the Internet Archive’s Vanishing Culture report about the importance of preservation in our digital age. I, of course, wrote about how we almost lost the GIFs:

The internet isn’t invisible. It’s a very physical thing encompassing mind-boggling maps of wires and undersea cables, and networks including countless privately owned and operated data centers — and in this current era of the web, where so-called “artificial intelligence” is causing an uptick in the environmental and human impacts of this technological infrastructure, it’s good to be reminded of the physicality of the digital world.

When somebody flips off the servers, as GeoCities did when it shuttered in the late 2000s, the world risks losing all artifacts of that culture if they’re not preserved. GIFs that seemed like they’d dance forever simply disappear.

What makes Monday’s update more than mere nostalgia fuel is how the semantic search works. It means more GIFs that had been saved without the most searchable file names are now, at long last, discoverable. The new system uses an open-source computer vision model called CLIP-ViT L/14, indeed developed by OpenAI, that processes what’s happening in each frame of a GIF to link that to plain-language search queries. (The monopoly that major “AI” companies have on research and development in the field is one crucial point raised by Karen Hao in her new book, “Empire of AI” — there are cases where specifically scoped and carefully applied models have genuine utility. But the ideologies shaping the field leave many such projects in the dust, as OpenAI and its ilk chase “AGI” in what Hao has described in her book as a quasi-religious quest.)

A few GIFs the author has archived in their personal collection, which spans dozens of categories and hundreds of GIFs gathered via GifCities since 2020-era lockdowns.

GifCities’s search results now feel less like a GIF slot machine and more like, well, an overview of what you actually searched. It’s the kind of “AI” application that doesn't make you want to throw your laptop out the window, even if I will miss the hours I spent down trial-and-error rabbit holes. (If you want to search by file name, you can still access that using the “special search” settings.)

In other contexts, CLIP models have well-documented bias issues. Indeed, they can perpetuate harmful stereotypes, especially around race and gender. But helping people find under construction signs in a digital archive? That’s about as benign as so-called “machine learning” gets. We’re not talking about biased hiring algorithms or invasive surveillance systems here; we’re talking about retrieving dancing hamsters from the annals of old internet whimsy. Better search tools mean fewer jittery, infinitely looping artifacts stay buried in the vast databases of our digital memory institutions.

As I wrote in my Vanishing Culture essay, “when we preserve and revisit the remnants of digital culture's recent history, it behooves us to remember that this networked realm, as imperfect and as frustrating as it can feel sometimes, is what we make it.”

The thing to talk about over your next power lunch:

On November 5, 1999, a small group of activists gathered outside the headquarters of a tech company in California to stage what The Atlantic called “the first time in human history that anyone has ever thought it worthwhile to stage an organized political protest, even a small one, over a mathematical algorithm.” They targeted Unisys, the company that held the patent for the LZW compression algorithm used in GIFs.

Yes, it was on its face an obscure demonstration. Burn All GIFs Day was about patent and royalty controversies around the algorithm that made GIFs possible. The activists couldn’t literally burn digital files due to state law about setting fires in public places, so they instead used red markers to ceremonially cross out GIF images on floppy disks instead. What seemed like a quirky tech protest about intellectual property law was actually a canary in the digital coal mine.

Twenty-six years later, we're facing far more consequential battles over digital control. Tech oligarchs are shoving generative “AI” products everywhere, trained on the intellectual property of countless creative workers on the way in and destabilizing the market for our work on the way out. Meanwhile, platforms are disrupted overnight when a rogue billionaire decides to take on a new pet project — buying a social network to amplify his own personal grudges.

The enshittification of the web feels relentless, almost inevitable.

But here's the thing: we are still netizens. When I see early internet GIFs, I am amused, yes. I’m pleased semantic search now makes it easier to find drag queen GIFs from websites past. It’s also a reminder that we collectively have more power to shape the development of these technologies than the Big Tech platforms want us to think.

The web is still what we make it — even when it doesn't feel that way.

When the Internet Archive's servers briefly went dark last October, it reminded me how fragile our digital memory really is. But it also revealed something powerful: how much we collectively depend on these vital institutions that preserve our digital culture. The coordinated attacks on archives aren’t coincidental — they’re targeting the infrastructure that lets us remember how things used to work, what we've lost and, crucially, what’s still possible.

GifCities might seem like a small thing in the face of platform monopolies and surveillance capitalism. But every tool that helps us access our digital history is also a tool for imagining different digital futures. The same technology that can help you find a 1999 GIF of a construction worker can help researchers understand how we learned to express ourselves online before algorithms decided what we should see.

Sexy construction workers. Jackhammers. Signs. The "under construction" niche is rich.

The deeper opportunity here is rekindling the notion of ourselves as netizens, not just users. Citizens of the internet with some collective responsibility for what these shared spaces become, not passive consumers of whatever Mark Zuckerberg or Elon Musk decides to serve us next.

Every GIF really is a gift, as the Internet Archive put it in its announcement of the new GifCities. But so is every act of digital preservation, every choice to support institutions that serve the public rather than shareholders, every moment we remember that the ideal for the web is something collective, that we build together — not something that happens to us while we doom-scroll through feeds designed to extract our attention and sell it to the highest bidder.

The challenge is also preserving the sense of possibility — that the internet could still become what those early “under construction” GIFs promised: a space we're all still working on, still figuring out, still building.

And one more long thing to read:

This TL;DR Briefing builds on analysis from the essay I contributed to the Internet Archive’s Vanishing Culture report last year, which I republished in full here in December on ESC KEY .CO, along with a new introduction about the broader attacks on libraries and archives that netizens need to keep an eye on: