Mattie Lubchansky tracked every weird thought in a doc, then turned it into the wildest book

For her second graphic novel, “Simplicity,” this acclaimed cartoonist and a former editor at The Nib tried a new approach: save any idea that intuitively seemed to “fit.” She did that for more than a year. We set the table to talk her process, a literal vision and making trans culture right now.

“What if the Shakers” — a utopian offshoot of the Quakers known for their communal living, gender equality and, indeed, celibacy — “had sex?!” It’s the kind of question that seems to have absolutely nothing to do with techno-fascist city states, which makes it the kind of absurd world-building connection that only ESC KEY .CO’s third Power Lunchee, Mattie Lubchansky, could make. It’s also kind of a lot to process.

The curious context for this quandary about the sex lives of the sexless Shakers is Lubchansky’s second graphic novel, “Simplicity,” out July 29 from Pantheon Books. It follows “Boys Weekend,” her 2023 horror sensation that landed on several big best-of-the-year book lists. With “Simplicity,” I wouldn’t be shocked if she chose that title partly so book reviewers could be baited into writing a dad-joke sentence such as, “‘Simplicity’ is, well, complex.” But it’s true. It threads together a speculative future about dystopian America in the 2080s that feels as wildly imaginative as it does uncomfortably present-tense.

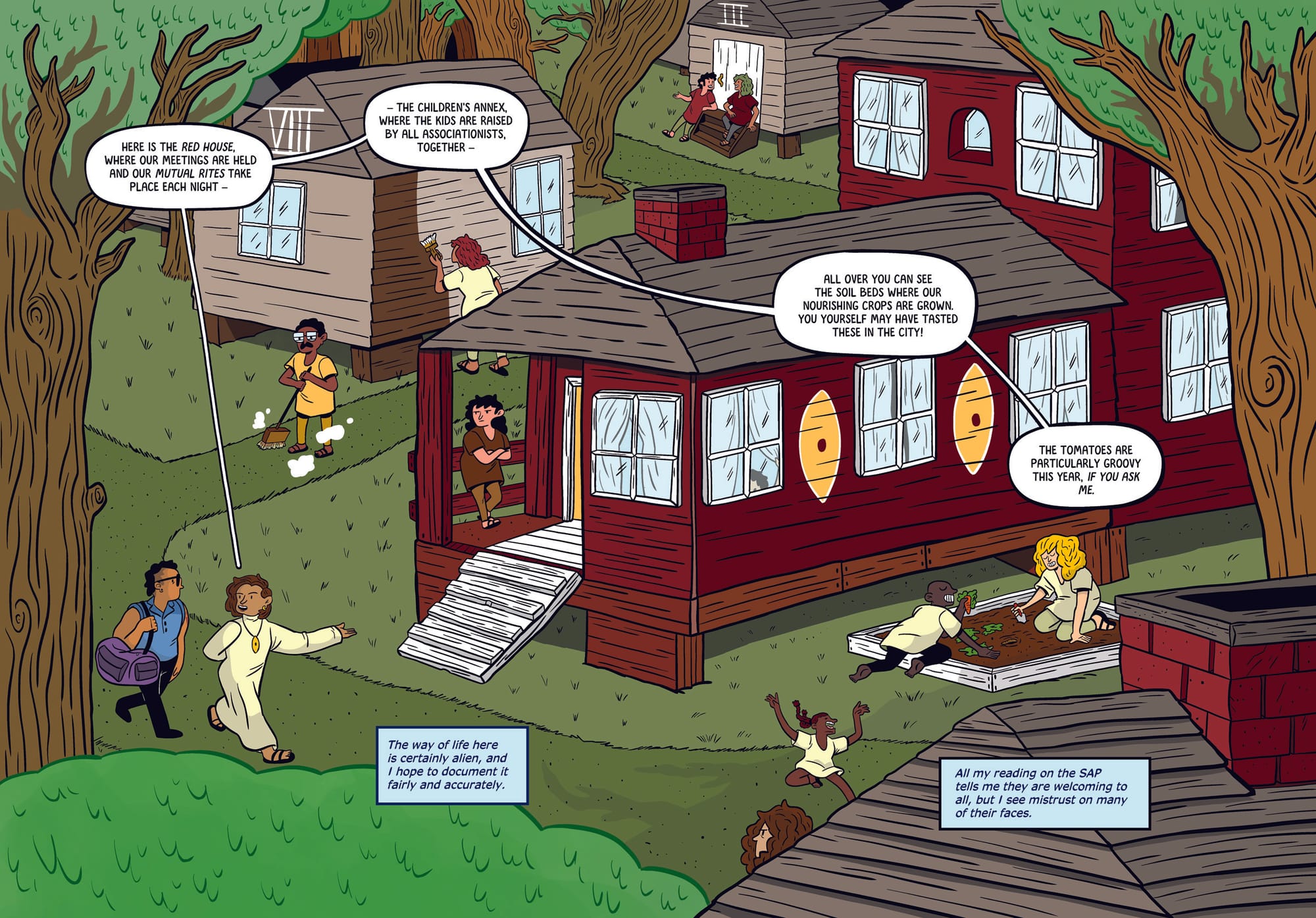

We meet our protagonist Lucius, a young anthropologist, in the walled New York City Administrative and Security Territory, founded after America’s formal dissolution in 2041. Lucius gets commissioned to study a hippie commune, the Spiritual Association of Peers, that’s survived in the Catskill Mountains since the 1970s. What starts as academic fieldwork becomes something more complicated when Lucius encounters the commune’s nightly ritual: the Mutual Rite, yes, an orgy. The Peers’ rejection of gender policing becomes a kind of liberation for Lucius, a trans man now outside the walls of the surveillance state. But soon, visions of monsters and the mysterious deaths of several community members suggest that utopia isn’t, ahem, so simple.

Lubchansky’s research into 19th-century American communitarian movements convinced her that “this need for community and safety, and the feeling that the world was ending, were all downstream of massive societal upheaval.” “The big thing about this time was not just the industrialization of America,” she tells me, “but what the invention of modern capitalism did to our lives, our relationship to work, society and community, period.”

In this way, her speculative future becomes a mirror for our present moment of institutional collapse and the search for alternative ways of being together.

It’s one of those books that sounds like it shouldn’t work when you try and label it. Equal parts science fiction, folk horror, political satire and call to revolution. But it somehow makes sense in the context of this page-turning plot.

When we lunch, Lubchansky is days away from her book tour, genuinely uncertain how “Simplicity” will be received by a world increasingly hostile to trans bodies and trans stories. She rejects so-called “respectability politics,” which feels both more urgent and more risky in 2025. And just as her book threads together many seemingly unrelated things, we manage to cover everything from cryptozoology to creative integrity to the process she followed to make a story so wonderfully weird. “It’s a big expression of the central idea of all my work: self-determination.”

There’s only one rule to Power Lunch: we are granted the power to lunch anywhere in the world, but the Power Lunchee must pick only one place where we will virtually gather. This rule is now in effect.

🍴🍴🍴

JD: You made it! Where in the world are you right now?

ML: I’m in beautiful Queens, New York, where I’ve lived for almost two decades now.

JD: Nice, I love Queens, every time I’m lucky enough to swing through.

ML: I am a big partisan for Queens. It is the world’s borough, baby. I’ll probably never leave. It’s the best.

JD: That raises the big question, where do you want us to go for lunch? We could go anywhere! But I get the sense that we’re sticking around Queens!

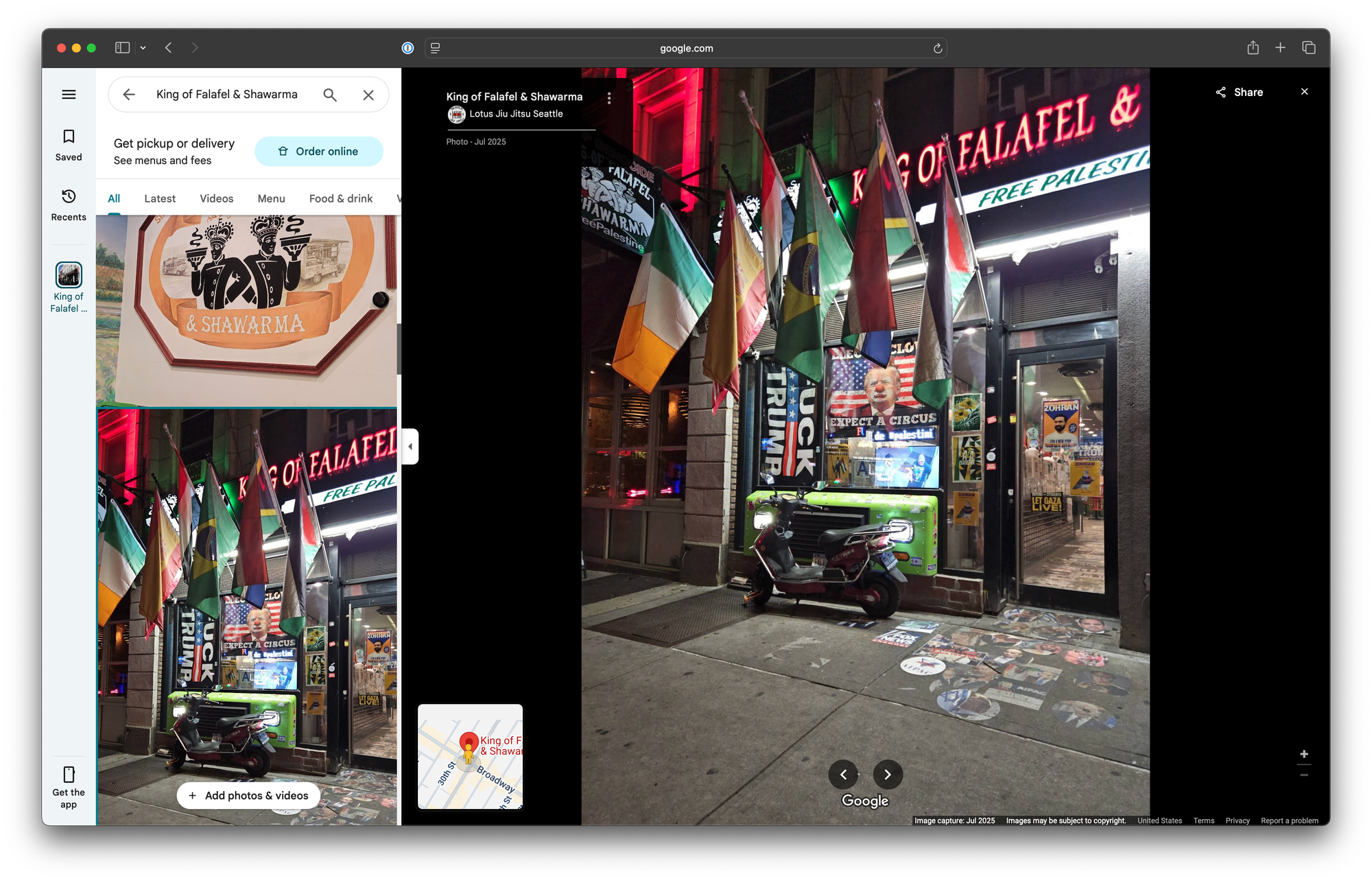

ML: I was thinking a lot about this, and I actually am deep at heart such a Queens supremacist that we’re sticking with the story of where I live. I want to take you to the King of Falafel & Shawarma on Broadway in Astoria, the best falafel on planet Earth, made by my man, Freddy!

JD: Shout out to Freddy! Yes! What are you going to order? You’ve already sold me on the falafel.

ML: Obviously, the falafel is incredible. It’s like no other falafel you’ve ever had. They will give you some extra falafel while you’re waiting for your food if you catch them at the right time, and they’re incredible fresh.

This Google Maps screenshot shows the exact location of where we did (not) go for Power Lunch, because Power Lunch is a speculative lunch. But you should totally go to King of Falafel & Shawarma the next time you're in Queens.

JD: Well, now that we’ve got the order in, we’re snacking on a couple of falafels while we’re waiting, and I have a question I’ve been dying to ask: is it true you have a Bigfoot tattoo?!

ML: I do! I have had a lifelong fascination with cryptids.

JD: I’ve always been fascinated by cryptids, too, and as a queer, I’ve felt there’s something queer about the intrigue of cryptids, monsters and such. One of the funniest things I ever did was go on a Bigfoot hunting trip when I was a travel editor in Oregon. We went into the Blue Mountains of eastern Oregon with this anthropologist guy. It was one of the most remote places I’d ever been.

And as I was recently reading your graphic novel, “Simplicity,” I kept thinking back to that trip for whatever reason and the similarly remote setting as the book. Then I read another interview where you had talked a bit about having a Bigfoot tattoo. It made me curious, what is it about creatures that exist in those spaces between known and unknown that appeals to you as an artist?

ML: I remember at my elementary school library, for some reason, we had a book that was like an oral history about cryptids, with interviews about cryptid encounters. Every chapter was a different cryptid. Why was this in an elementary school library? I don’t know! But we had it. When I was 8, I used to check it out every week so I could read the whole thing cover to cover. I was really obsessed with it.

And honestly, I was a scared kid. I was scared of cryptids, monsters, aliens. I watched the film “Alien” when I was young, and it scared the absolute bejesus out of me. But it is maybe my favorite movie at this point.

So, I’ve always had this fear of, and fascination with, these unclassifiable things. I think maybe that’s the queer fascination with this stuff, too. It exists and it doesn’t. It’s scary and it’s not, and it exists in this space where it’s plausibly deniable that they’re real.

I don’t think Bigfoot is capital-r real. It’s probably just bears waking up from hibernation because they look like guys walking around when they’re skinny.

But as someone with an overactive imagination, I relate to this subsuming things we actually see to something sort of fantastical.

“I started jotting down all these notes in a Google Doc that grew to be 30 to 40 pages long.”

JD: On the subject of overactive imaginations, your new book fuses a lot of seemingly disparate elements: a speculative future about fascist city states; utopian separatist communities and cults; gender liberation and oppression; anthropology; the evolution of police uniform design; hell, even a critique of museums as an instrument of power. There’s a lot going on here. And you connect it all beautifully through a story that’s both sprawling and intimate, sharply satirical with heartfelt characters. It’s the kind of thing that makes you think, how’d she do that?! I’m curious, what process led you to connecting these particular dots?

ML: Speculative future is, to me, not an intentional process. That’s simply where I live in my brain at all times. When I’m sitting down to write, I want to figure out how to get some gore, some monsters, or a flying car, something. It’s always where I’m living with my visual imagination.

But this book started out with an idea for the main character, Lucius, and these ecstatic visions he has in the book. That’s where I started. I mean, I had a similar thing happen that he does in the book: I just had the vision, wholesale. And I spun it out from that vision, like, who is this? Where does he come from? Where is he going?

I started thinking about separatism. I was talking to Calvin Kasulke, who is a novelist and a close friend of mine. He was telling me about this book called “Paradise Now: The Story of American Utopianism” by Chris Jennings, which is about all these 19th-century pre-Marxist communes.

And as I was reading that, I started jotting down all these notes in a Google Doc that grew to be 30 to 40 pages long of sentences I wrote down: things from that book but also conversations with people, thoughts I had randomly walking around, things from watching movies and TV shows, anything that I felt could fit into this project.

That doc became this big, unnamed hole that I was throwing things into for a year and a half. I had this big pile of stuff, and then I spent a long time sifting through it and turning it into a novel. It was a lot of rewriting and a lot of adding and subtracting.

Compared with my first book, “Boys Weekend” — which was more straightforwardly based on a thing that happened to me with clear characters — this assemblage was a new process for me. They say that writing any book is actually learning how to write that book, right? I’m definitely not the first person to say that, but it’s very true.

JD: Where did museums come into all of this? Because it becomes an elegant framing device when you open the story in a museum, and then each chapter begins with an artifact on display in that museum. It’s world building and also sharply satirical.

ML: It was at the last minute when I added all the stuff about the museums. I was thinking a lot about history: what it is, who it’s for, who makes it and who consumes it.

I was inspired by Kelly Reichardt’s film, “First Cow,” where the first thing you see is the skeletons of the two main characters. So you’ve got this thing in your brain at the start of the story. Not only are they going to die, but history is going to wash over these guys just like every other person in the story. Just like everybody you know currently. Just like you. It is. You are also subject to the institutional and cultural forces that you were born into, the ones that will eventually kill you; they’re there already. You can fight to change them, and you should. But history comes for us all, and I wanted to instill that in the book. I didn’t want to use that same exact framing, but that mood.

Then, right after that, I was at the American Museum of Natural History here in New York. There’s all this stuff on display there from when it was first built where they’ve kept it but indicated where it is wrong — and they’ve kept it on purpose. For instance, there’s a diorama of the sale of Manhattan, which is a very apocryphal thing. It’s covered in these stickers that say, “What’s wrong with this?” with lines drawn to details that are historically inaccurate.

I was so fascinated by that. I started thinking about museums a lot. Then it wormed its way into the book pretty significantly.

“I was in museums all the time ... I’ve been in a lot of empty museums alone.”

JD: As someone who’s fascinated by museums, the good and bad, it felt like the kind of story told by someone who’s spent a lot of time in museums.

ML: Well, I actually used to work in museums.

Before I was a cartoonist, I worked as an assistant to a glass blower. And before I was an assistant to a glass blower, I worked as an engineer.

My engineering job was designing HVAC systems for museums. And so I was in museums all the time. Even my wife, who is a journalist, worked in the communications department for a museum for a while.

I’ve been in a lot of empty museums alone.

JD: On your research: that intuitive “this fits?! so I put it in a Google Doc” process is fascinating to me as an Apple Notes idea hoarder. What’s the weirdest rabbit hole you went down?

ML: The big rabbit hole was how close the Shakers were to getting it right! A lot of the Spiritual Association of Peers in the book is like if you combined the Shakers with followers of this French thinker, Étienne Cabet, whose people kept trying to found utopias in America based on a novel he wrote.

But the Shakers had a real community going. People would go live there just because it was a solid place to get three meals a day. There was real community, low crime. Then obviously the sex thing was a problem. They were celibate, which is why they died out.

They were called Shakers because they were the “Shaking Quakers.” At their weekly meetings, they’d get nude and run around screaming. They had to get their energy out somehow.

The nightly orgy in my book is me goofing around with that idea. What if the Shakers had sex? I think they'd still be around. They were onto something.

JD: There were moments in the book that made me literally laugh out loud. The “Los San Frangeles Security Territory” line made me chuckle. Tell me about that speculative future thinking.

ML: You’d have to be under a rock not to notice society is fraying, right? It has been for basically my entire life. You can trace a very straight line from how politics went in the early to late ’70s and early ’80s to right now.

I’m inspired by Margaret Atwood’s approach: if you take today and nothing changes, what does 25 years from now look like?

As things get worse and environmental catastrophe worsens, the instinct for people in power is to build walls and consolidate. Why wouldn’t we end up with walled city-states?

“I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the eye if I toned anything down based on what I thought people’s reactions would be.”

JD: One thing I admire about your work, especially with this book, is how you reject so-called “respectability politics.” You so openly depict queer and trans intimacy without explaining or censoring anything for the cishets. But when you’re writing a book for a major publisher — Pantheon Books is an imprint of Penguin Random House — and reaching a wider audience, have you found it challenging to avoid the kind of censorship we’ve come to expect from so many media and institutions?

ML: All I can say is, let’s see! Talk to me in a few days, when the book is out, because I really don’t know what that’s going to be like.

Generally, though, I’ve never been seriously censored by any publication, partly due to my own obstinacy and partly luck. Matt Bors, my former editor at The Nib, let me do whatever I wanted. Anna Kaufman at Pantheon believes in my work and has never edited me for ideology or graphic content. And I feel kind of strongly that Anna took quite chance on this book in acquiring it. Because who knows how things are going to go, frankly? I worry about the future.

There are a lot of nude trans people having sex in this book. You see a close-up of a trans guy’s bottom growth. I’m not shying away from what trans bodies look like. It’s important for me to show that. Who knows if I’ll get in trouble for it. But politically I wouldn’t be able to look myself in the eye if I toned anything down based on what I thought people’s reactions would be.

“Something this book is about is, what do you do when all they want is to put clamps on you?”

JD: It really is a horny book. There was a moment reading it where I texted my friend with benefits just to see what they were doing…

ML: [Cracks up, interrupts] That makes me so happy!

JD: It’s horny in a smart and refreshing way, too. So it functions on a few levels, and it makes me wonder: is there some intended message there with the juxtaposition of pleasure and dystopia? Or am I reading too deeply into what are wonderfully illustrated cartoon orgies, to your credit?

ML: Thank you! Well, something this book is about is, what do you do when all they want is to put clamps on you?

Everything about society right now is surveillance and control of people’s bodies. But what is the stuff of being alive? Having control of your own life and body, in a world that has enough for everybody. Being in control of your body involves fucking. I want the future to have that.

Among queer people, among trans people, I personally hate the language that “just existing is radical.” And yet, it’s true: they don’t want you to exist.

But I don’t know why you’d deprive yourself just because the motherfuckers want you dead. They’ve always wanted you dead. Let there be bread and roses and orgies! It’s a big expression of the central idea of all my work: self-determination.

JD: There's a moment where the protagonist takes a research job for a big evil company and has a falling out with an ex. That ethical tension felt painfully contemporary. Where did that come from?

ML: It’s me arguing with myself. So much of this book is about how people get radicalized: what takes somebody from going with the flow but feeling uncomfortable, to who you see at the end waking up and fighting?

That “I gotta eat, I can’t let ethics dictate how I act” thing — I think a lot of people see themselves in that. It’s me sometimes too. The ex who gets in the argument is more where I’m at politically, but like me if I were a huge asshole about it. That central conflict, seeing things are broken but not thinking about your role in fixing them, is something a lot of people wrestle with.

JD: You’re about to spend weeks on a book tour. What’s a question you’re hoping someone will ask that no one has asked yet?

ML: Nobody’s asked about the setting of “Simplicity” specifically. I could talk about the summer camp I went to as a teenager and how the gong in the book is a real gong at a real place.

🍴🍴🍴

JD: A little dessert is always a good idea, right?

ML: Yeah. Yeah.

JD: Correct! Anything else we want to grab from King of Falafel as an after-lunch treat?

ML: I’d say let’s grab a Salaam Cola or Yemonade, which are the Coke product alternatives because of the boycott. King of Falafel is a Palestinian restaurant, and I love them very much. And Yemonade is delicious!

On the Salaam website, they picture their delicious canned sodas in a range of scenic settings. Here are two Yemonades. Because there were two of us at this Power Lunch.

JD: Make that two Yemonades, please!