The state of fashion week amid polycrisis: Dispatch from my anxiety attack at a catwalk show

This London Fashion Week has been a dazzling display of global design talent in the U.K. capital. Emerging designers turned heads. There was that upcycled parachute gown. And street style for days. But this recap is about an anxiety attack I had. Before the one show that, ultimately, gave me chills.

When an editor has an anxiety attack at fashion week, the editor should probably go home. Instead, I put on sunglasses indoors, and not for any semblance of the Wintour effect, I wish to stress.

Fashion is an industry built on many of the same underlying power dynamics and global networks of exploitation as colonial empires. Few people at fashion weeks want to talk about that. The problems are vast, and those working to address them are often dismissed as doing trivial work by people who underestimate their own role in the system. This is an industry driving textile waste visible from space; promoting Big Oil’s agenda by churning out more fossil-fuel clothes than the world’s population could possibly wear; and trapping garment workers in grueling jobs that do not pay living wages.

It’s true: Having worked as an editor in the sector for four years, the state of fashion endlessly frustrates me. And yet, this is not all that I was having an anxiety attack about.

Few things move me like witnessing an emerging designer’s catwalk show at London Fashion Week: seeing talents who try to build independent brands that avoid repeating the same harms as the labels before them. When you’re not even thinking about their sustainability credentials because of the mesmerizing sartorial story unfolding before you, that’s when you know this is a name to watch.

The British Fashion Council also challenged, in some ways, the dominance of the new. Runways from Oxfam, Vinted and eBay elevated secondhand and vintage fashion to its rightful place, where the creativity inherent in curation was the point. And must I mention the actual dame turning heads and garnering headlines in a bright red parachute upcycled into a gown by Vin + Omi? Theatrical, silly, smirk-inducing. All of this is endlessly thrilling if you love style.

Yes, modern fashion events can sometimes seem like they’re in service of algorithms — “IRL” activations that appear to have a primary goal of prompting content for our social media feeds, observed live through the screens of our phones as we record rather than being present. Yet even so, there’s nothing like being there, seeing a young designer’s rise firsthand. No matter the state of the world, those joys persist.

London Fashion Week ends Monday, and I’ve been tubing and power-walking my way across the city from event to catwalk to panel to catwalk. That means more than a few crowded rooms, holding a coffee or a cocktail depending on the hour. It’s generally fine. My extroverted side loves talking to strangers about their outfits, the stories behind the garments and objects they’ve adorned themselves with. But in those acutely anxious moments, when the overstimulation makes me shut down, my neurospicy side zooms out to 30,000 feet; I imagine myself as a kind of nihilistic ethnographer embedded in, yet separate from, what I’m seeing. I chuckle sometimes at my own contradictions: give me a mic and a room, and I enter performance mode, determined to ensure we all have a ball. But put me in an unstructured crowd of strangers when I’m on the verge of a full-blown anxiety attack, which I am known to have from time to time, and I wilt like a wallflower philosopher in shades.

“Fashion is language, and fashion is also political speech.”

There have been a few young designers’ shows this fashion week that have served as escapism from all that. Pauline Dujancourt’s romantic knitwear was one such ethereal, enchanting experience. People-watching the crowds at London Fashion Week is another such joy: the styles, the aesthetic codes, how deeply people can communicate nonverbally through what they wear.

As I surveyed the cocktail crowd in the minutes before the doors opened to enter the showroom, I found myself meditating on fashion not only for the style, the cultural capital, the problems. But also its power of expression.

With the mega-luxury groups, that expression is more often one of class and wealth. (One such expression might be: “Yes, I can afford all this Louis Vuitton monogrammed luggage.” Thrilling!)

But for designers such as Katharine Hamnett, who I saw speak on a panel at Tank magazine in Fitzrovia on Friday evening, the power can also be subversive. Hamnett has designed T-shirts, hoodies and totes with bold-typeface slogans such as “NO ARMS TO ISRAEL” to support the Palestine Solidarity Campaign, wearing one such shirt for the panel. That panel also featured Daniel Mawuli Quist, the Ghanaian creative director of The Or Foundation, which works to stop waste colonialism, and Kazna Asker, a British-Yemeni designer who was the first to present a Hijabi collection at the Central Saint Martins fashion show in 2022.

Fashion is language, and fashion is also political speech. And as much as London Fashion Week presented joyful and galvanizing moments, the mood this year was, for me, a little more fraught than in prior years. It’s hard to get really excited about, say, knitwear when the world feels like it’s on fire. (That, I admit, is not a helpful perspective.)

But as I picked a cocktail off the bar counter at 180 Studios in the Strand last night, I couldn’t help but feel like I wanted to scream. I imagined, momentarily, the entire room screaming with me. A scream symphony.

At this point, I realized I was spiraling into doomer vibes. Doomer vibes don’t help anyone, either. Feeling bad about a thing has never changed a thing unless those bad feelings precede action. That’s not an excuse to carry on with business as usual. It’s a rallying cry — a reminder to snap out of the self-centered worry that serves no one but those whose power you seek to challenge.

When someone says “it’s pointless to enjoy X because of Y,” that’s someone who is not going to be fun at either a party or a protest. “It’s pointless to enjoy a silly queer rave because of the uptick in homophobia and transphobia” would miss the point of radical joy. “It’s pointless to talk about personal style with fascism on the rise” would miss the point of life’s small moments; the life-saving affirmation of a young trans person’s full self; of having a fucking ball, darling. “It’s pointless to talk about fast fashion’s ills when [insert anything that seems worse here]” would miss the point of interbeing, a concept coined by Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh to describe the interconnectedness of all things.

When someone says, “it’s pointless to get dressed when you should be in a fatal pit of despair” — well, let me admit that last one was the depressed state of mind I was in after picking up a second cocktail and retreating to the corner of the room by the skincare brand activation, where it was easy to hide since no one was paying attention to the skincare brand.

This is the moment I slid on the shades, a pair of ’90s Prada frames I got at the Cancer Research charity shop in Chelsea, a great place to raid rich people’s closets, if you will. As a working-class kid from Appalachia, America’s coal country, I am often surprised by the rooms I’ve managed to find myself in over the course of my (confusingly diverse) editorial career. My first “job” — as I wrote in a letter in January about how not to leave America — was throwing bales of hay on the tractor’s wagon, 50 cents per bale thrown. On the right days, that inspires pride. On the wrong days, it provokes flight, as in: I do not belong here. The problems rumbling around in the back of my mind aren’t high-fashion problems. They are, more often, student loan and can’t-afford-a-mortgage-while-I’m-single problems. Nonbinary bisexual problems. Queer immigrant problems.

The thing about spiraling at fashion week is that you’re never spiraling about just fashion week. You’re spiraling about everything fashion week lets you not think about until suddenly you are thinking about it all at once, in a room full of people who didn’t come here to think about it, either.

“None of this was happening at fashion week. But all of it was there with me.”

Karen Attiah’s firing had been rattling around my head. Eleven years at The Washington Post, terminated for Bluesky posts about America’s ritualized responses to political violence. She'd written nothing false (“we live in a country that accepts white children being massacred by gun violence”); nothing incendiary (“for everyone saying political violence has no place in this country … remember two Democratic legislators were shot in Minnesota just this year. America shrugged and moved on”); just observed that we perform the same hollow dance every time: “thoughts and prayers,” “this is not who we are,” absolve, forget, repeat. The Post called this “gross misconduct.”

Jimmy Kimmel’s suspension came later, a comedian pulled from air after the Charlie Kirk shooting commentary, following pressure from a president seemingly “obsessed” with late-night TV hosts.

Then the news about the FBI reportedly preparing to classify trans people as “Violent Extremists.”

Then the proposed bill that would let Marco Rubio revoke U.S. citizens’ passports for “political speech.”

None of this was happening at fashion week. But all of it was there with me, creating this doubling: watching models in what you could label as “gender-fluid” garments while knowing many people in power are actively advocating to categorize me and my friends as a domestic terror threat; listening to panels about speaking truth to power while colleagues lose jobs for repeating the words the man actually said; loving style but unable to grapple with the underlying industry's avoidance of accountability.

The crowd left the cocktail rooms. The doors were opening for the show, which turned out to be the highlight of the week for me.

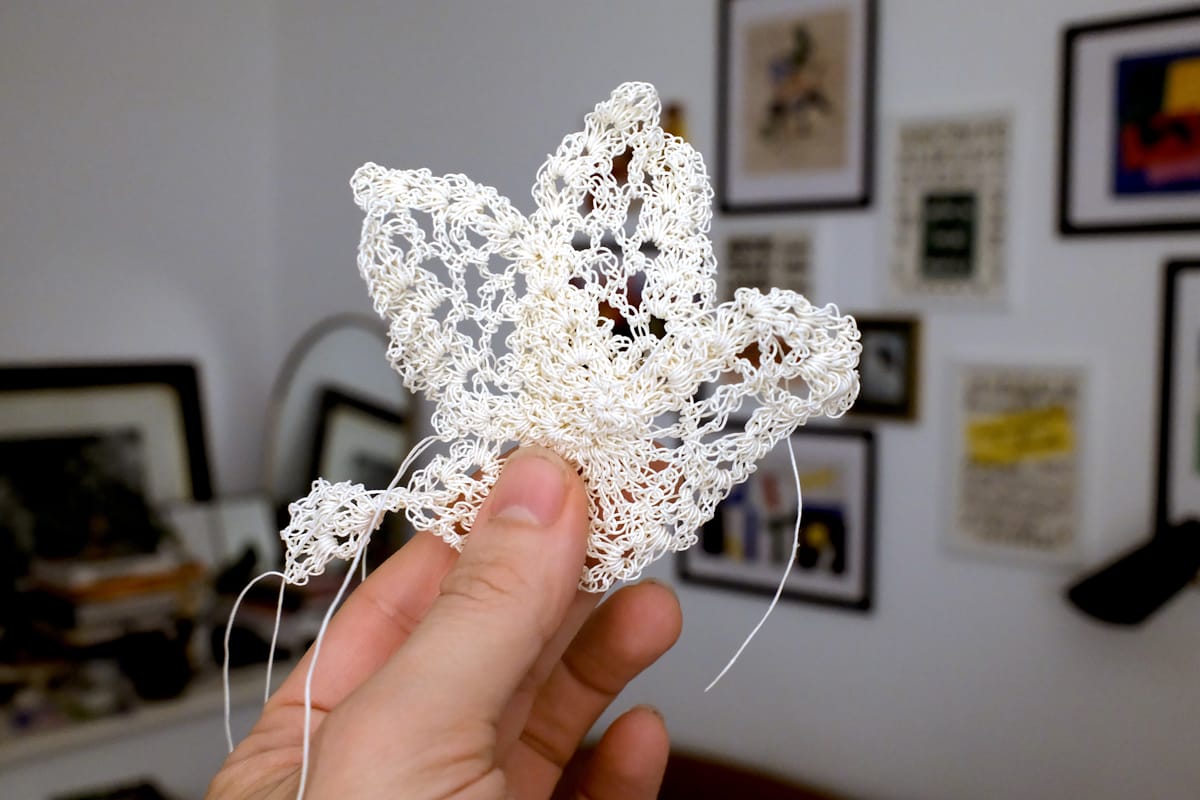

Dujancourt’s collection was beautiful in a way that makes one forget, momentarily, about everything outside the room. This may have been the second show for her namesake label, but her world of lace we entered was fully realized and multidimensional.

The designer built an entire language from knitting, referencing the kind my Appalachian grandmother might have done — a sweet nod to the domestic labor of women worldwide. It filtered through with a slight club kid sensibility, dancing with shadows from wedding gown-like silhouettes.

One reference point for her ready-to-wear collection is the character Nina Mikhailovna Zarechnaya in Anton Chekhov’s “The Seagull,” a role she once played while studying theater in Paris, as Liam Hess reported in Vogue. Her collection carried a palpable sense of grief, theatricality and sensual presence. I was left with a feeling of life in the afterworld, where the beloved is gone, where beautiful things remain beautiful but in a different light. Loss lingers. Life still brings joy. The subtly gothic, subtly grandmotherly collection held such emotional truths simultaneously.

After the show, I walked out onto the Strand. September in London does this thing where it can’t decide if it’s summer or autumn, so it just sits there, damp and uncertain. I thought about my draft for this essay, sitting unfinished on my laptop. Wondering how to write about fashion week without making it a metaphor for everything, but also without pretending it exists in some sealed cultural space. How to reflect on what one might take away from fashion weeks in 2025, when the far more urgent concerns remain immigration raids, mutual aid for our trans and queer communities, and a free Palestine.

The truth is, I don’t know how to resolve the contradictions. As with elements of Dujancourt's show, I am left pondering the juxtapositions.

Indeed, I work in industries built on exploitation while critiquing that exploitation here.

And, personally, I worry about securing a U.K. passport before the Labour government extends the residency years, while the U.S. government seeks power to, one might safely presume, revoke passports for those who call a genocide a genocide — all while still holding the kind of passport that opens most borders.

The distance between my Appalachian childhood, those hay bales, those gas station years, and this London fashion circuit can’t be bridged by any clean narrative about class mobility or professional success. The censoring of comedians and journalists, the weaponizing of the FBI toward trans people — things not seen in my lifetime in the United States — is the context for everything. You can’t deny it. You can’t fully escape it, either.

“Gestures toward different possibilities, different relationships with stuff, with style, with the exhausting apparatus.”

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe the anxiety attack wasn’t about resolving anything. Maybe it was my body’s way of saying: this is all happening at once — the handcrafted garments and the passport threats, the emerging designers and the FBI classifications, the radical reimaginings of gender and the government’s violent response to those reimaginings. They exist in the same timeline, sometimes the same rooms. It is beguiling. It is sick. It is the world we are in.

The Oxfam and eBay shows, the BFC’s stellar class of NewGen designers, the cathartic Tank magazine panel. These weren’t solutions, but they were something. Gestures toward different possibilities, different relationships with stuff, with style, with the exhausting apparatus.

I walked back toward the Holborn tube station, past the tourists who’d never know fashion week was happening. Tomorrow I’d write this up properly.

But tonight, I was on the street: neither here nor there, neither fashion insider nor complete outsider, holding contradictions that refuse to resolve into anything as clean as an ending.

The next show would start when it did. I’d go. Of course I’d go.

Not because I think fashion is appropriate resistance or meaningful confrontation, though at times it may be.

Just because this is where I happen to be, doing the work I happen to do, in the historical moment we happen to be living through, where we’re all performing different kinds of drag for different kinds of audiences.

The anxiety had passed. It would come back. These things do.

It’s probably good I didn’t go to an after-party.

Fashion week continued.