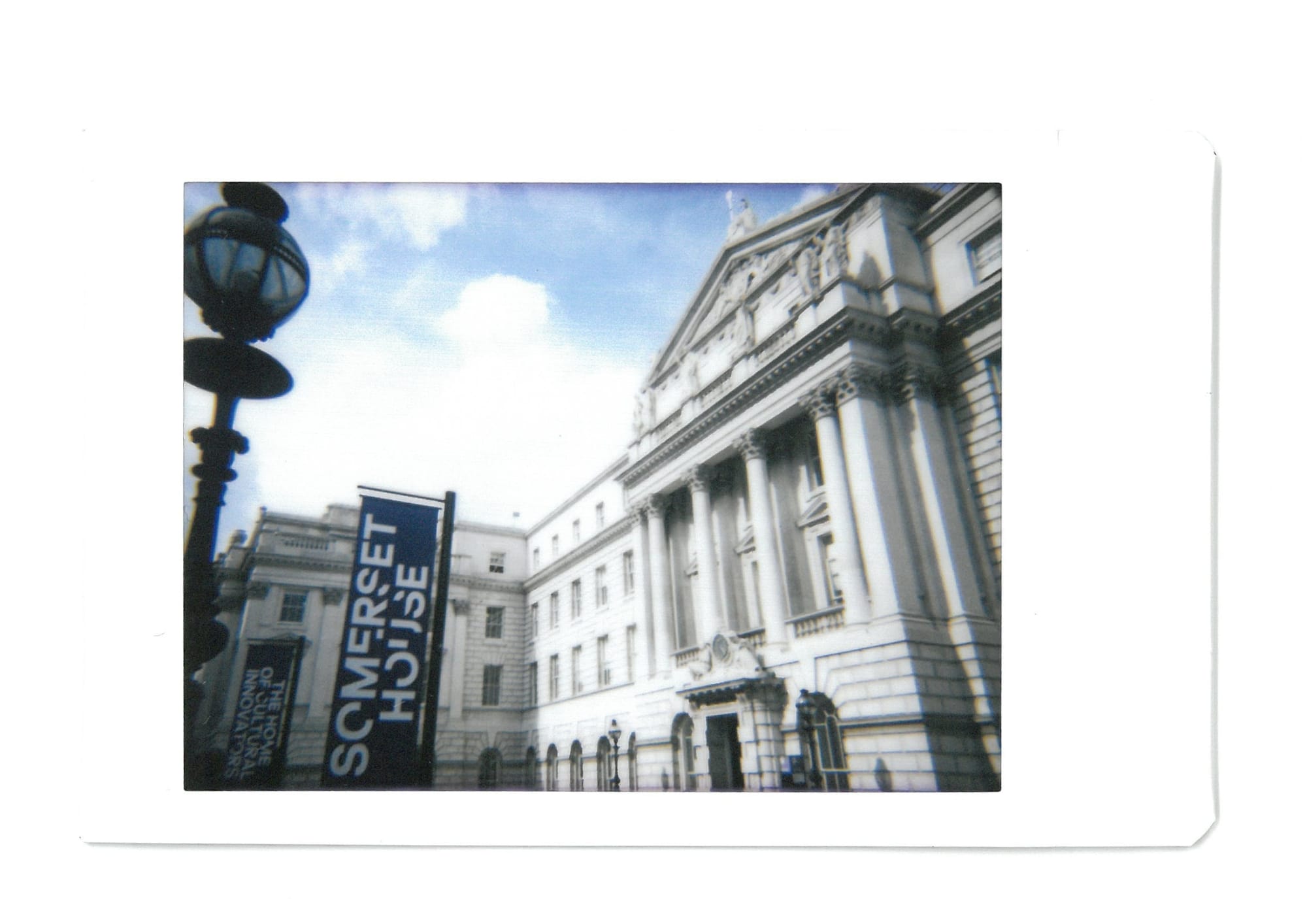

Fed up with bullshit? Try finding your people: Snapshots from our night at Somerset House

On Thursday, ESC KEY .CO brought our Clean Creatives reporting to life with a soft-launch event at Somerset House. We called out bullshit, mapped greenwashing tactics and took instant photos. Most importantly, we found our people. Turns out, community can be more than a buzzword.

Somerset House recently opened a new waterfront bar and art pavilion — Setlist — overlooking the Thames. And since I work out of this supportive and incredibly grand arts center, housed in a Neoclassical building on the Strand in central London, I get 15% off at Setlist. Thursday at about half past 4 p.m., I felt quite anxious, so I stepped out to get some air. I, of course, remembered the discount. (Growing up a working class kid in coal country, I never neglect a discount, trust me.) So, a few staircases and paces later, I was on the terrace with a discounted IPA in hand. I sat at a big table alone, overlooking the river outside my office. I gazed through my cheap instant camera’s viewfinder at the perspirating pint glass in the late May sun. “This would be a really cliched photo,” I mumbled to myself. I plonked the camera back down on the table. I didn’t trust any of my ideas. I was in the throes of an anxiety attack. After a few friends had canceled, I was worried that absolutely no one else would come to the event I was cohosting in just a couple hours.

The event, “Call Out the BS,” brought to life reporting I’ve been doing in the past few months for an ESC KEY .CO long-read, which I published on Monday, focused on the Clean Creatives movement to end fossil fuel advertising, media and PR. Over the last several weeks, I’d been speaking with the campaign’s organizers, ex-F-List agency leads, and creatives using satire and stunts to expose PR and advertising industry work for fossil fuel clients. Clean Creatives had recently adapted a popular NYC Climate Week workshop as a DIY resource, and it explored how creative workers could respond to the intersectionality of the overlapping bad things happening in the year of our lord 2025: yes, the rolling back of climate action and the repeating of anti-science disinformation from the leaders of powerful countries. But also the world’s most powerful corporations’ bow toward fascism — rolling back not only climate targets but support for racial justice, LGBTQ+ people, gender equality, you name a good thing and it seems at risk. It’s so overwhelming, it’s enough to leave you feeling defeated — and alone.

As a journalist and strategist, my first instinct was to get to the bottom of this story. How are creative workers banding together to respond? How do we fight the fatigue and use our voices, even when we feel isolated and exhausted? After all, our voices may be the only things we’ve got, as one Clean Creatives campaigner told me for last week’s Power Tools feature. And while no single creative worker can change massive systems by themselves, together, we have a greater chance of making a dent and collectively applying pressure through direct action. And so merely using my pen, figuratively speaking, didn’t feel like enough this time.

Behind the scenes, this was one of those assignments where the reporter became subject to the story: I, too, was feeling totally tired. Online conversations about intersectional climate justice didn’t feel like enough. A newsletter long-read didn’t feel like enough. Everyone I interviewed stressed to me how important keywords like “community” and “finding your people” were, and some said you “can’t go it alone.” And yet, here I was feeling quite alone in the process.

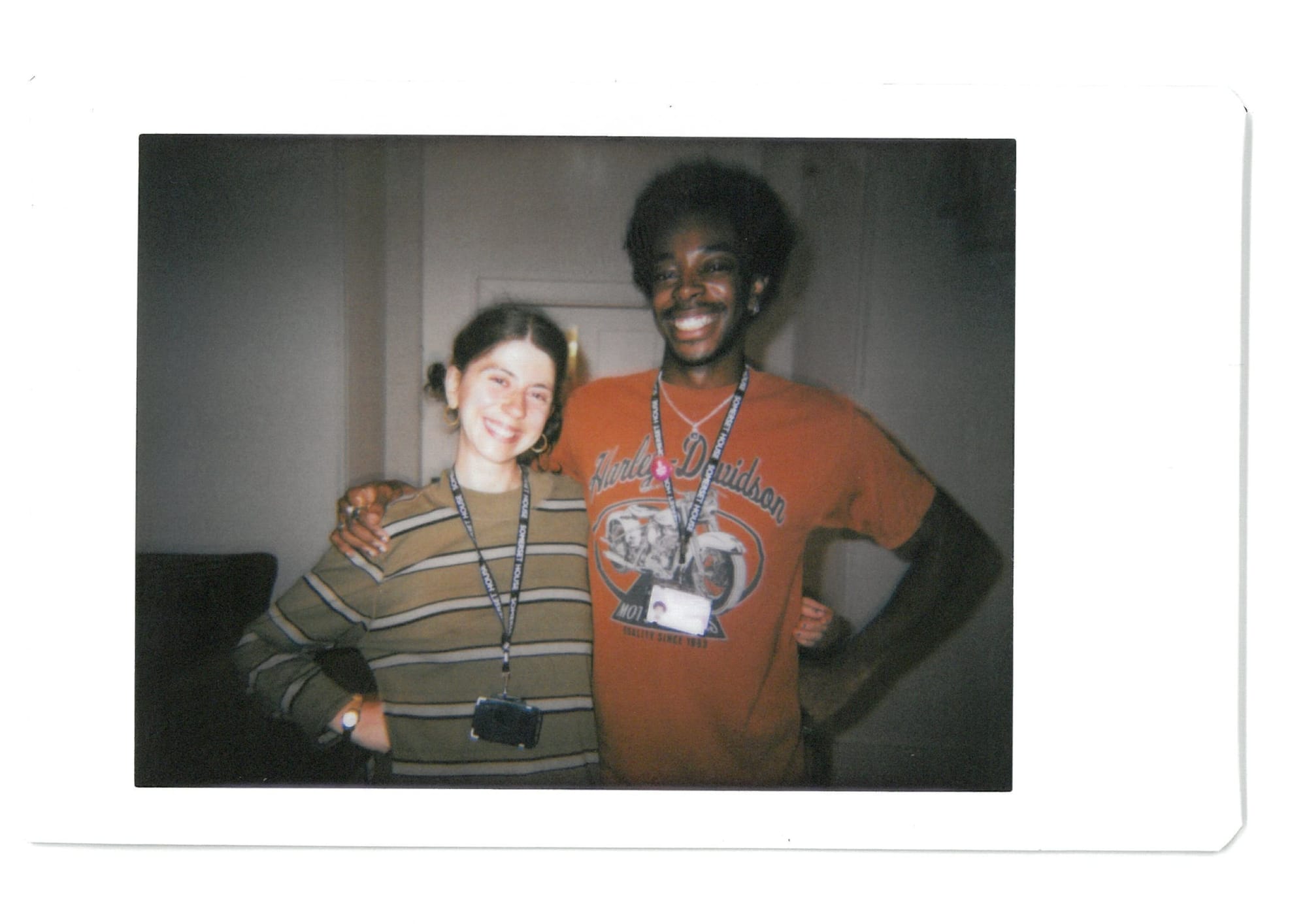

The author at Somerset House with the very first person who arrived.

That was the impetus for me to ask Laura Ranzato, organizing director of Clean Creatives and one of my sources for last week’s story, if they’d be down for bringing this material to life through an IRL event? I mean, I was craving the kind of community that climate campaigners were telling me was so important and yet I wasn’t finding in my daily life, especially as a self-employed person working remotely for clients and publications (and you, dear reader). Why not bring the principle to life, then? Ranzato got on a call with me. “Of course!” she said, immediately. Somerset House Exchange, the co-working space in the basement of the New Wing, agreed to host. And within a few days, Ranzato had introduced me to the folks at Wholegrain Digital, a London-based web design firm founded by Tom and Vineeta Greenwood — the people behind the Sustainable Web Manifesto. I’d long admired their work. Turned out, we shared the same office. Over the next few weeks, Wholegrain’s Bailey Bryan, the firm’s new business manager, collaborated with me on a shared slide deck for a few short talks we would present at the event — all about trying to align climate truths, human rights and values with our work as creatives, strategists, designers and, yes, sometimes anxious writers.

After a long sip of IPA, I scrolled through the slides again on my iPhone, then glancing over the notes I’d scrawled in an old notebook. What if despite the reporting, the outreach, the support from Clean Creatives and Wholegrain, maybe nobody would actually show up?! I compulsively cracked both my knuckles. The stakes were heightened in my mind because I’d also promoted this event to early readers as the “ESC KEY .CO soft-launch.” What if the soft launch was so soft it was imperceptible? What if, indeed, I was not only failing as a newsletter writer but also failing as the co-host of an event for a movement I cared so deeply about that I’d dedicate a whole article to? What if I had been wasting everyone’s time?! Shrug emoticons flashed like flurries in my line of sight.

I wasn’t only dealing with a silly bout of imposter syndrome — or my inner saboteur, as one host of a reality drag TV show might put it. “What if nobody really cares? What if finding your people is the impossible first step because … we’re actually all alone in the bullshit?” It was a familiar, pesky feeling.

Another sip, and I was suddenly 21, in the back of a van on a several-hour road trip through West Virginia, heading to the Changing of the Leaves Festival on what was left of Kayford Mountain. The small protest music event was hosted annually at the family farm of the late anti-coal environmental activist, Larry Gibson. I was, in retrospect, ungifted at stringed instruments despite a decade of instruction.

The fight against fossil fuels is a topic that I have a deeply personal interest in given I grew up in the Appalachian Mountains, aka America’s coal country. (Ergo, I also have asthma.) In the lead up to that van ride, I’d hardly felt so alone. I was working part-time at an Appalachian arts center. And despite the creative community around me I had as a young musician, I had come into a greater awareness of what was wrong with the world, it broke my heart, then. People often said I was “melancholic” from a young age, which felt like a euphemism even before I knew what “euphemism” meant — perhaps, more so troubled by the state of the communities I grew up in, our poverty, our abuse from extractive industries, oh what little wealth stayed in our mountains. I loved our mountains. Another fact that made me feel so alone is that I’d known from a young age that I was queer, and I knew that was a very bad thing to be around here. I was only “out” to a handful of people in my life, and I felt like the whole of the mountain world I so dearly loved hated me.

In a way, that trip to perform at the festival, in which I filled in — very badly — as the violinist for a local acoustic band, changed the trajectory of my young life. Gibson — who had spent his entire career fighting mountaintop removal mining — had an old farm perched on part of a mountain that no longer existed. The rest of it had been blown to bits by big mining corporations, rich guys who didn’t live around here — all at great cost to the people and environment around the destroyed landscapes. Sitting on a hill, overlooking the crater of a lost mountain peak, I was surrounded by people who deeply cared about the moral tragedy we were witnessing. I was troubled. But I was not alone. An elder in my eyes, the wise Gibson had demonstrated to me that no matter if the world thought we were nobodies, we could mobilize others and stand up to the powerful interests imposing on all the things you held dear. (Gibson, president of the Keeper of the Mountains Foundation and lifetime member of the Sierra Club, died one year later at the age of 66.)

My calendar notification dinged that it was 5 p.m. and about time for me to go back inside. The pizza would be arriving soon. I ripped up the notes I’d made. I remembered how I felt at 21, how I was terrible at the violin and thought somehow I could make a difference playing that violin at a protest festival. “Get over yourself,” I thought to myself. “What would your younger self have to say to you right now? Get on with it! Play the instrument, even if you are really bad!”

Turns out, a lot of other people feel like I do about the state of our world. Rather than letting down Bailey and Ranzato (and an entire movement!), several dozen people actually showed up. IRL! Wow! As folks munched on vegan and vegetarian slices from Pizza Pilgrims, I asked everyone to take a seat for a short talk. Almost all the seats were full. I was like, what?!?!

At the front of the room, I began by briefly recounting the backstory of the first essay I had ever published what felt like eons ago, at least in journalist time. It was about that anti-mountaintop removal protest in Appalachia, a short piece I wrote when I was 21 for a rare local news project, which had recently gotten grant funding from the Knight Foundation.

Before walking back inside from Setlist, I’d ended down a Wayback Machine rabbit hole looking for that first essay I had ever published. I found it, reread it and despite the sappy, earnest tone, it sounded much like I felt today:

They say you can see this from outer-space; I believe it. I’m hiking up a trail in the rural mountains of Appalachia. The last five hours have been spent in a van navigating the country roads of West Virginia to get to the Changing of the Leaves Festival on what is left of Kayford Mountain. Larry Gibson’s family land is 50 acres of what once was the lowest point on this mountain. Now I stand on a narrow ridge overlooking what is considered to be the largest mountaintop removal site in all of Appalachia. There is a man in front of me reeling off numbers and citing statistics to prove the moral evils of what I am seeing. Yet no words are needed to do that. What he says becomes muffled as I am engrossed in the scene before me—an entire mountain gone.

Gibson is by no means a young man, but he possesses an exuberant energy, a strong desire to share his story and work. He’s taken his property and turned it into a remote place where visitors can experience the evils of mountaintop removal through a variety of gatherings. Witnessing such destruction first hand is quite the experience.

Nothing can capture the emotion I feel when I survey a mountain scene lacking a mountain. Gibson once described these feelings in an interview, “The young eyes of the day will never see what I’ve seen. No, the young eyes of the day will never see the mountains with no limits, no boundaries to where you could roam.”

The man who has taken my group of friends up to see this terrible scene points at a few more mountains that are set to be destroyed. I question what it is that prompts humankind to do such a thing. I feel strongly that this is not exclusively an environmental issue. No one that has come here fits a stereotype. The people here come from many walks of life and many geographical regions. What brings them together is the concern for these mountains, these majestic things once described as immovable. Few talk about the evils of coal as a resource; the diverse conversations I overhear primarily center on the idea that this is not just an energy issue or an environmental issue, but a moral issue. It stems from greed—coal corporations that seek only profit, abusing rural communities and taking advantage of their legal rights. As I spend the day in such caring, hospitable company, I realize that this movement is only trying to stop the destruction because these people recognize the right thing they need to do. Here it's not faith that is moving mountains; here the faithful are working to save them.

I read that line again: “This movement is only trying to stop the destruction because these people recognize the right thing they need to do.” Damn, OK, fair play, young JD!

I had been unproductively wallowing in my feelings about how bad things are to the degree that I almost forgot I have some agency — I have my creativity. And even if a few people show up, we should never underestimate the power of a few creative people coming together.

I may have been a shit musician — believe me, please, I was — but I can at the very least bring some likeminded people together in a room. And in the process, we can remind each other that “community” can be more than a buzzword. It can be, well, a community. You show up. You get better at recognizing the patterns of powerful bullshit. And then, just maybe, you get a little more energy to do something about it together.

On Thursday, our gathering carried the same energy I’d felt back then on Kayford Mountain. After our talk, we hung out, added each other on LinkedIn (hey), talked about new collaborations and a few of you told me how good it felt to be in the same room, a little SZA playing in the background. At the very least, we took some cool instant photographs.

“You really do look like you spent a decade in Portland,” my friend Robbie, one of the first three people to arrive, told me when he saw the retro camera slung around my neck. My 21-year-old self would’ve been stoked by the instant photography.

Going back to it again today, I will add that the first half of the conclusion to my old essay was just ... OK:

As the evening draws closer and the sun droops in the sky, we pack our instruments into the back of the van and climb onboard for the long trip home. For the first while everyone keeps quiet. It’s hard to speak about this issue because it seems so overwhelming, so inhuman. Yet what I’ve seen at the Changing of the Leaves Festival is that a large part of the fight is the fight to recognize the powerful voice each of us possess. This is where it starts. Sometimes, like in my case, it might take a few songs at a little music festival to recognize that there’s an important role I need to play in this movement.

I won’t pick it apart. But then the final line betrayed my adorably ignorant wide-eyed hopes:

If I can help save a few mountains with singing, I’ll keep doing it until I lose my voice.

Sure, babes. I want to give you a hug, then a lecture. It’s funny because your music was bad. And none of your songs saved any mountains. Almost 14 years later and you’re no longer making music, which is probably best for everyone. None of that’s a failure. But the music, the festival, the whole road trip wasn’t only about saving mountains, anyway. It was reminding you that you can’t do anything without finding people to do it with. Sometimes, all you need is a vanful of friends. And you can join along even if you’re really bad at violin.

While I’m no longer aspiring to be a touring musician — praise be — I was a little hoarse on Friday morning after thanking everyone who showed up. You all reminded me of the possibilities for collective action.