Why Substack is nudging you to follow your ex, your hookups, randos who aren’t even writers

Last week, I got a creepy notification nudging me to follow an ex — on Substack. Then I realized how comprehensively the app had scraped my phone's contacts, a la the dark patterns of the monopoly-chasing social platforms that came before. My first question was, when had I ever consented to this?!

Let me begin by saying, there are numerous reasons this new media outlet will never be hosted on Substack. Chief of all: I don’t want you to call this “a Substack.”

But the list of reasons is longer than that and growing longer. Last week, I added a few more. Firstly, following news of Substack’s unicorn valuation, outrage ensued over the latest Nazi controversy on the platform. It has roiled media industry discourses. Secondly, I received an email nudge that brought back olfactory memories of a heartache past. Those two things aren’t directly related. And yet, upon closer inspection, they are linked — together, they show us what Substack wants to become.

Therefore, for the latest installment of the experimental BTS @ ESC series, we’re doing something a little different than our norm: I remix the typical structure of our TL;DR Briefing for a deeper personal meditation on what these dark patterns tell us about Substack and its direction of travel.

This is not a piece telling you to leave Substack. But this is a look into why writers and readers should worry about getting locked into another venture capitalist’s walled garden full of carnivorous plants designed to efficiently eat your eyeballs raw.

And per the usual, we still leave you with something to talk about at your next power lunch — in fact, we leave you with three things to ponder about the future of media.

The thing is:

This past week, I realized the problems with Substack are oddly captured in a parable about my overactively romantic but often unrequited heart. First, it’s relevant to know that nearly two years ago, I briefly dated an East London creative agency guy who almost exclusively wore varying shades of beige. He shall hereafter be known as Beige.

I was amused at Beige’s zealous commitment to this monochromaticity. I also liked his aroma: I recall green like foliage and a few understated cut flowers with base notes of some horny-sounding species of rare wood. He had the kind of facial structure strangers would compliment as “striking” and “gorgeous.” He’d get glances whenever we went out together along Broadway Market in London Fields. Invariably, in the small hours, we’d make out in the tunnel beneath the dripping train overpass, shelter from the mid-autumn drizzle — mere steps from the brewery’s door, where we were the last two people kicked out at closing time on a Wednesday. Eros accelerated by a few too many pints of Forest Road lager. This went on for more than a month. I knew I was falling in love.

But Beige was still processing a breakup from the summer before us. It was gradually apparent to me that he was still stewing in that heartache, with little room for someone new. And so following much deliberation with my astrological twin, I decided to stop seeing him. After all, feeling like you’re in a largely one-sided relationship, with a drip-campaign of occasional reciprocity, is distinctly and devastatingly heart-breaking — even when you are the one who makes the call to end it.

Several months after we stopped “hanging out,” I needed no user-experience (UX) nudge to have obsessive thoughts about him, including whenever I was on a date with someone else. He was there, a taupe phantom in my peripheral vision — an off-white ghost in freshly steamed linen. But if I were going to get a nudge to dive deeper into this limerence, then, it would obviously be a notification from TikTok suggesting this guy in your contacts is also on TikTok, and you should check him out.

Fortuitous? Or destiny?! Either way, there I was, on Beige’s page, several videos about bouquet arrangement later, half way down the feed of posts on his profile, the inevitable happened: My clumsy fingers accidentally liked a video. I panicked. Then I unliked the video and closed the app. Block him so he won’t see you being creepy! I thought. So I blocked him. But maybe he’ll notice you blocked him?! So then I unblocked him. That would need to be my last engagement with Beige, I thought.

I’ve come to expect these kinds of dark UX patterns from monopoly-chasing social media apps. It’s a user-growth model that Meta “perfected” in various ways. Facebook, for instance, has long wanted access to your contacts so it can suggest new people to “friend” on the platform. Expanding each user’s social graph on the app is essential to keeping you engaged, and engagement is key to its advertising business model. You probably use such apps knowing they’re free because your attention is their product.

“There's a new monopoly-chasing unicorn social media app nudging me to reconnect with people I've dated. That app is Substack.”

TikTok may be less of a conventional “social” network than Facebook. It’s not really a place you go to hang out with friends as it is a kind of user-generated, algorithmically curated television — an intensely personalized feed tailored to you based on your in-app behaviors. Most people on TikTok are consumers of content, which they occasionally share with friends. Even better if you DM within TikTok itself rather than leaving to DM on another app. TikTok wants your contacts so it can detain you longer within its walls.

To get access to your contacts, any social media app needs your consent. They’ll bug you until they get it from you. You often forget you gave it.

Fast forward two years and now there's a new monopoly-chasing unicorn “social media” app that’s nudging me to reconnect with people I’ve dated, people who happen to stay in my contacts, and that app is Substack. Such contact harvesting makes a little more sense on apps where you’re used to engaging with friends. It seems weirder coming from a newsletter app, although Substack never really aspired to be “just” a newsletter app.

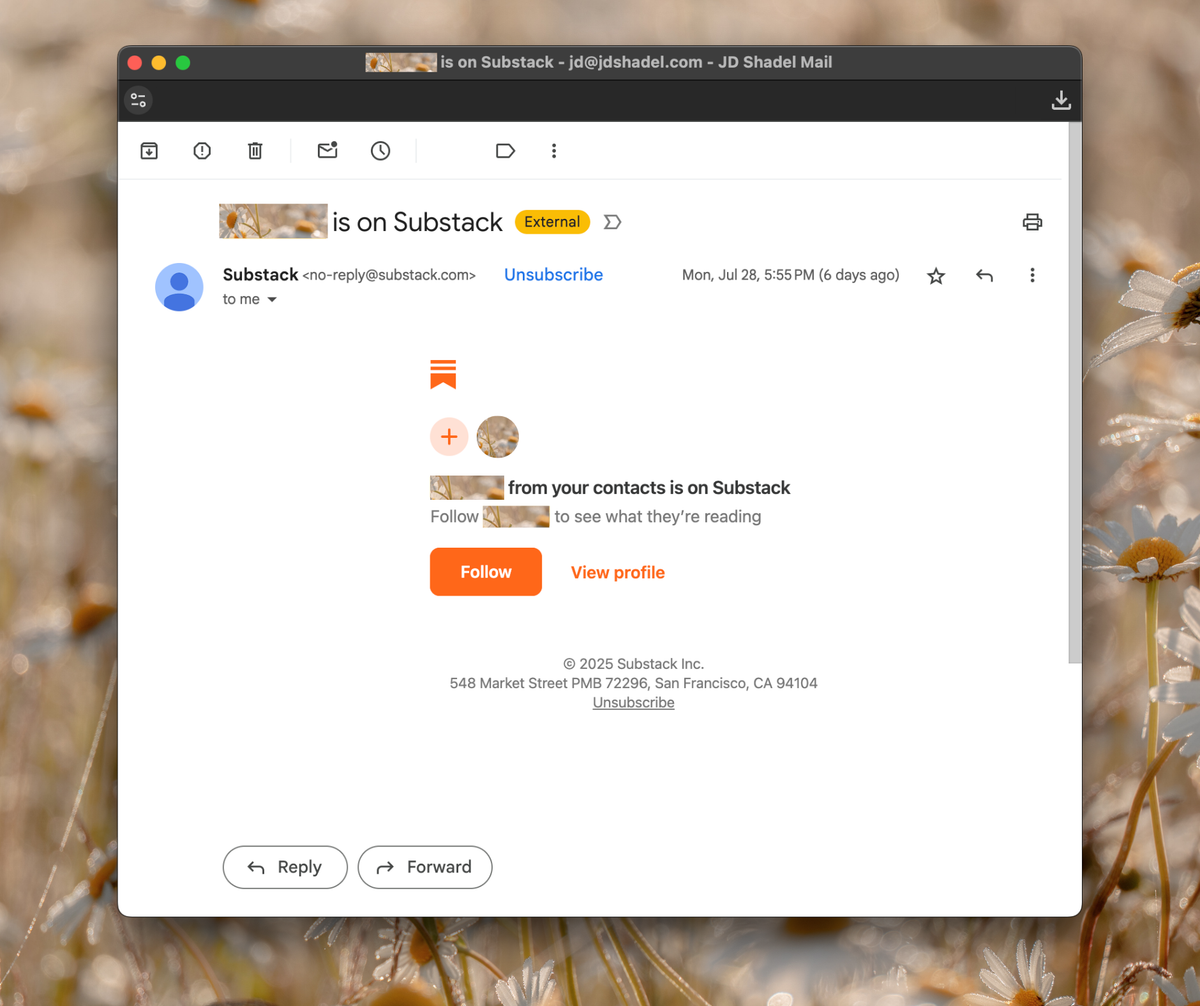

So, last week — fresh off news of Substack’s unicorn-level $1.1 billion valuation — I received a hauntingly familiar email: a nudge to follow a person I dated … on Substack. No, he’s not a writer. No, he does not post. He only subscribes to a handful of newsletters (one appears to be about flowers). Yes, he once downloaded the app and shared his contacts with the network, as did I even though I can’t remember consenting to it.

This social network-esque notification was, to me, the most intimate signal yet that made Substack’s ambitions clear: get you following your exes, one night stands and random connections from a night out — who don’t even write newsletters.

The thing about that is:

Indeed, this was the first time that I’d received a notification from Substack to follow someone I’d hooked up with. But this was not the first time Substack had sent me an email suggesting I follow someone I know. Substack frequently sends me a notification that X or Y writer has posted a new “Note,” and that I should “follow” Z journalist friend on the platform — a la Facebook’s emails begging you to log back in to see a post from your nemesis, or an in-app nudge to “friend” the person your ex cheated on you with a decade ago, the latter which happened recently to a dear friend.

If you’re a newsletter writer who cares about growing your email list, Substack’s increasing tendency to encourage users to “follow” is arguably the more egregious of all these nudges. By creating profiles for your readers that other readers can follow and DM in the app, Substack is building a new network lock-in effect where your potential readers are not encouraged to primarily “subscribe” to your newsletter as much as they are nudged to “follow” you. (A few months ago, an acquaintance told me they thought they had subscribed to this publication but weren’t getting the newsletters, to which I had to remind them I don’t publish on Substack and “following” JD Shadel on Substack is not the same thing as subscribing to ESC KEY .CO.)

As a reader, none of this may seem particularly problematic to you. And even some writers have used these native social features to great success, forging a community on the app that a newsletter itself could not achieve. I don’t doubt that. But I found the whole trajectory of the app concerning in a familiar way. Right now, writers on Substack can take their newsletter lists with them, but “follows” have no portable value. It’s one of the main reasons I did not launch this new media outlet, ESC KEY .CO, on Substack: I chose to build a custom website and newsletter using Ghost, the open-source content management system. I didn’t want to launch an independent publication on yet another Big Tech platform aiming to create a so-called “attention economy,” yet another endless-scroll casino becoming more and more out of step with its users once they’re in the door.

“This is all possible because of the profiles Substack generates, arguably nonconsensually, for everyone on the platform.”

Along with its follow feature, Substack also introduced Twitter-lite “Notes” and an algorithmic feed that aims to keep its writers’ readers within its walls. And on those walls, the writing has been clear enough that Substack wants to be akin to the other social media unicorns — a place to amass media power; to centralize “independent” publishing; to create an algorithmic kingmaker to influence political and cultural discourses, broadly speaking. It may have started primarily as a place for newsletters, but Substack instead seems like it’s positioning itself to become social media for an era where everyone is encouraged to become a Substacker including Nazis. Unlike, say, Ghost’s 2025 foray into the fediverse, Substack’s social features have no interoperability outside its own network, itself increasingly dominated by “AI” slop. Substack’s core job is to keep users locked in, then extract as much value out of them as possible. It’s why Substack’s chosen medium has evolved beyond words to become a host for live video and podcasts, as well. Most recently, the company’s U-turn on advertising makes perfect sense, too. It’s also why the app is spamming not only a writer’s audience but their reader’s contacts who are also on the app.

This is all possible because of the profiles Substack generates, arguably nonconsensually, for everyone on the platform, writers and readers alike. This includes countless readers who never knew their presence would be so visible on the app and website, or that they might be the subject of automated network-building email and notification campaigns.

If you subscribe or interact with content on the platform, even if you don’t technically have a publication on Substack, you have a profile on Substack. These profiles are visible to anyone. Unlike publications, which can be made private, profile pages cannot be made private. And if you’re in someone’s phone contacts who is also on Substack, it’s quite likely both of you have consented to being the subject of an email suggesting you follow the other on Substack.

Substack launched this “Contact Matching” feature in 2023. The company wrote then in its company newsletter, On Substack:

Following helps writers grow their audience via the Substack network, which is already home to millions of the world’s most valuable readers. We built this feature to help maximize — and not replace — subscriptions, which will always be the most important type of relationship on Substack.

“I want to grow my network, not connect with my aunt Judie and the local pizza place.”

—Cezar Capacle

Certainly, the growth of any media business, whether it’s an independent newsletter or the legacy glossies, depends on the strength of subscriber relationships (to monetize directly through reader revenue, through advertising or both). The benefit of newsletters is that they operate on an open protocol that no one controls. Therefore, the publisher “owns” that relationship with readers and, in theory, publishing is largely unmitigated by algorithmic intrusion (this is, to a degree, changing, as our inboxes are increasingly the site of “AI” intervention through email clients such as Gmail). It’s not that Substack’s social media features can’t benefit some writers on its platform. It’s that this particular execution of network effects feels so random, so Facebook, so ick. In the comments section to that official Substack post announcing the new features, one user — Cezar Capacle, a tabletop games designer — replied:

I don’t think you [i.e., Substack] understand how different my audience and my interests are from my contact list. I want to grow my network, not connect with my aunt Judie and the local pizza place.

For many readers, the contact matching feature has felt like a pesky intrusion into their privacy. Frustrated, some have taken to Reddit to complain — confused as to how they consented to it. It’s not surprising that people are complaining about something on Reddit but it underscores the fact that many people didn’t realize what they’d actually agreed to. “I also find it very hard to believe I ever would’ve accepted that. So many websites ask you to sync contacts and I always decline,” one Redditor wrote in the comments to a post in the r/Substack subreddit with the title “Ok what the fuck.” The OP was alarmed that their boss was among their connections now on Substack whenever they went to share an article.

Yes, users have technically consented. But it’s hardly informed consent when nobody realizes what, exactly, they’re consenting to — and in its actions, the platform reveals what it hopes to become.

Where things get interesting: really cringe:

At first, I held my breath when I got that email suggesting I follow the guy I’d dated. Then I laughed and posted about it to a private Slack group of journalists I’m in via Project C. But a few days later, I realized the problem went deeper when I discovered the extent to which Substack had inhaled my love life, devoid of all context.

I was scanning my inbox on July 31st. Since many of the writers I follow have newsletters on Substack, I often read in the Substack app. I opened the latest issue of Idle Thoughts, the personal newsletter by Shon Faye. I then tapped to read it in the app, where I’ve also gotten into the habit of bookmarking posts. I read half the post, “writing tips,” then, of course, bookmarked it. I then went to share it with a friend who writes a newsletter for writers. I tapped the “share” icon and my jaw dropped.

In the share pop-up, there was a scrollable list of faces, i.e., people on Substack I could share the post with. Expectedly, I saw the faces of several colleagues who write excellent Substack newsletters. But also there in the first five faces was the profile picture of a guy I hooked up with once off of Grindr, an American photographer who had moved to Tuscany to work with wineries — we’d had a magical evening at a few bars in a less touristy corner of Florence two summers ago. (He read me some of his poetry in bed, then we exchanged numbers and never spoke again.) Next to him were the two Eds that I had been falling in love with, one Ed in winter and the other Ed in spring. I scrolled further and saw the dancer, the producer and the actor figuring out his next career move. There was even the face of one guy I matched with on Hinge, but never went on a date with. And then, of course, there was Beige.

“At this time, the option to un-sync or remove contacts you've uploaded to Substack is not available.”

—Substack

Yes, part of the issue is how many queers who read are in my contacts. But I felt I should also not need to be reminded of all these people every time I read an article in what was, once upon a time, primarily a newsletter app.

The good news is that you can turn off contact matching … to a point. Tap your profile picture in the upper right corner. Then tap the gear icon in the lower right corner. Then tap the “Privacy & Safety” menu. Under “Contact Matching,” you can toggle on/off the feature.

The bad news is that all those contacts Substack imported when you “consented” to this will be there in your app for evermore, as Substack’s help article on the subject reads: “At this time, the option to un-sync or remove contacts you've uploaded to Substack is not available.” In other words, it’s significantly easier getting a free mail-order STI test in London on the National Health Service and receiving treatment for the clap (which all can be done without seeing a doctor directly) than it is to get the ghosts of hookups past off your Substack app.

It’s a sick coincidence that this personal saga unfolded the same week as Substack’s latest Nazi controversy, which revealed just how dark these engagement-driven systems can get when poorly moderated and regulated.

The app that nudged me to follow a long lost romantic connection also sent swastika-branded push notifications to unsuspecting users’ phones. The former is cringe. The latter is indisputably evil. The two things seem unrelated. But they stem from the same underlying business model. And together, the two vastly different episodes speak to Substack’s trajectory.

Taylor Lorenz’s investigation found that Substack sent alerts promoting “NatSocToday,” a newsletter serving “the National Socialist and White Nationalist Community,” complete with Holocaust denial content and calls to eradicate minorities to create a “White homeland,” Lorenz reported in her scoop. It was the predictable outcome of recommendation systems designed to maximize engagement at any cost. The same users who clicked on the Nazi newsletter out of shock or alarm were then algorithmically directed to related white nationalist content, including another publication that was featured on Substack’s “Rising in History” leaderboard.

As Casey Newton explained in January 2024 when his newsletter, Platformer, left Substack over another Nazi content controversy: “We’ve seen this movie before — and we won’t stick around to watch it play out.” The platform’s recommendation systems and algorithmic feeds mean the company actively promotes content rather than neutrally hosting it.

Substack’s $1.1 billion valuation rewards precisely these seemingly disparate dark patterns. The latest funding round from BOND and The Chernin Group valued the company at 24 times its $45 million annual recurring revenue, a premium that suggests investors see massive growth potential in Substack’s transformation from newsletter service to social media platform.

All of this added together — the contact harvesting, algorithmic feeds and engagement optimization — represent much of Silicon Valley’s standard surveillance capitalism playbook.

Yes, we’ve seen this movie before — and it’s certainly not a rom-com.

The thing three things to talk about over your next power lunch:

I’m left with three key questions as we watch this latest venture-fueled rampage in media unfold.

“Newly independent media figures are now described as launching ‘a Substack’ rather than their own publication or media outlet.”

First, any conversation on the subject needs to be framed with this one: what does a healthy independent media ecosystem actually look like? Because, as Lex Roman argued in their newsletter, Journalists Pay Themselves, “a monopoly is brewing” with Substack’s new unicorn valuation. Newly independent media figures are now described as launching “a Substack” rather than their own publication or media outlet. “Terry Moran could have launched his media brand, but he launched ‘a Substack,’ according to Axios,” Roman wrote. Similarly, they noted that the media framed Jim Acosta’s move into self-publishing as “head[ing] to Substack” rather than launching an independent publication. The list goes on. “‘Read my Substack’ is a now ubiquitous catchphrase,” they wrote.

The platform has successfully made its brand bigger than the writers using it, a classic Big Tech move that concentrates cultural power while claiming to democratize it.

The irony is profound. Writers flee traditional media’s corporate constraints and billionaire owners only to build audiences on a venture-backed platform with its own set of algorithmic puppet strings and far-right agendas. Substack operates as a closed ecosystem where “all it takes is one board member to say, ‘you should really be showing more messages about XYZ’ for Substack’s feed to look completely different,” Roman warns. We’ve seen this play out before with FKA Twitter and Elon Musk, Facebook and Cambridge Analytica. A single point of control will always be controlled.

Secondly, a tricky one that certainly isn’t unique to Substack but becomes a conundrum for our gentrified internet of “platforms”: can readers support independent writers without becoming products themselves? The answer to this one gets to the heart of why I chose the open-source CMS Ghost to build our own platform for ESC KEY .CO: Even readers who want to support independent journalism on Substack cannot easily avoid being enrolled in Substack’s contact-harvesting campaigns. There’s no opt-out from being publicly on Substack (as even I technically am, given I do subscribe to several Substack newsletters, including Lorenz’s User Mag).

“There’s no opt-out from being publicly on Substack, as even I technically am.”

As Roman has also documented, the platform pushes readers toward its app, where “smart notifications” encourage users to opt out of email entirely. It’s a textbook lock-in strategy that transforms independent publishers into dependent tenants. One could technically leave now with those email addresses intact, but as Substack makes the app the home for reader relationships, there’s no guarantee of smooth sailing in the future.

That said, there’s a difference between calling Substack’s leaders and investors out for their bullshit and harassing writers on Substack, those still on the platform argue. Lorenz addressed this in a post last week on Bluesky:

Bombarding hard working content creators and independent journalists with personal attacks instead of criticizing the people in power who run these platforms is counterproductive and harmful. Especially the women and LGBTQ creators.

Thirdly, one should ask, why are venture capitalists betting hundreds of millions on a platform that profits from extremism? Well, one could answer that by merely reframing the question as a declarative statement (i.e., “venture capitalists are betting hundreds of millions of dollars on a platform that profits from extremism”).

Substack’s content moderation failures aren’t accidental. Rather, they’re baked into a business model that takes 10% of all subscription revenue including, we must conclude, from Nazi newsletters. And the company’s “free speech” positioning provides perfect cover for this arrangement. By claiming ideological commitment to open discourse, Substack deflects criticism of its financial dependence on controversial content that drives engagement and subscriptions.

“We’re witnessing the familiar Silicon Valley story of ‘embrace, extend, extinguish’ applied to newsletter publishing.”

Consequently, many writers genuinely seeking to build independent media careers have become unwitting participants in a system that undermines the very independence they’re pursuing. They’re building audiences on borrowed land, subject to algorithmic whims and platform policies they cannot directly influence, while helping to subsidize the infrastructure that promotes their ideological opponents.

That’s all not so different from other Big Tech companies, you could interject, and you’d be right.

We’re witnessing the familiar Silicon Valley story of “embrace, extend, extinguish” applied to newsletter publishing. Substack embraced writers fleeing traditional media, extended their reach through social features and recommendation systems, and now works to extinguish their ability to leave by making readers into platform users rather than portable email subscribers.

Two years later, I still think about Beige sometimes, not because I’m pining for unreciprocated romance, but because his ghost in my phone has become a strange metaphor for how these platforms operate. They take our most private connections and turn them into growth vectors: a gentle ping that masks an invasive system designed to keep us scrolling, clicking, engaging all for the benefit of the platform.

One sillier question I’m quietly left with is, I wonder if Beige has ever received a notification to follow me? And if he did, did he recall my scent as viscerally as I did his?

And one more long thing to read:

I hope you have a power lunch planned soon. But if you don’t, worry not! This is the Summer of Lunch here at ESC KEY .CO, and next week we’re returning with yet another profile of a creative mind navigating this weird era. Last week, we set the table for an iconic Power Lunch with the acclaimed cartoonist Mattie Lubchansky and her new graphic novel, “Simplicity.” It’s a nice palette cleanser if you’d rather think about orgies in the context of a near-future dystopia rather than our current far-right billionaire internet dystopia.